When Logic Meets Art…

Art was an unfamiliar world to me. My interests lay in fields that demanded logical and structured thinking, such as computer science and mathematics. In 2023, I met a special child who changed my perspective on art entirely.

I was volunteering with a nonprofit organization, helping children with disabilities with their learning. Among them, there was one child who spoke very little and struggled to interact with others in class. The moment that child picked up a pencil and touched it to paper, everything changed. It wasn’t just doodling. Shapes and colors seemed to come to life. In that moment, I realized this child was communicating with the world not through words but through art.

That experience led me to see art as more than just a means of expression. I began to perceive it as another language that reflects human thought processes and emotions. I became deeply interested in how art serves as a medium for children with disabilities and how their creativity manifests. This curiosity drove me to independently study art, delving into its history, techniques, and cognitive science aspects. This book is the result of that journey.

This is not just a book on art theory. It is an exploration of my personal curiosity, sparked by a child's drawings, that led me to examine the world of art through both a logical and emotional lens. I hope this study provides a fresh perspective on understanding art and offers intriguing discoveries for those who, like me, were once unfamiliar with it.

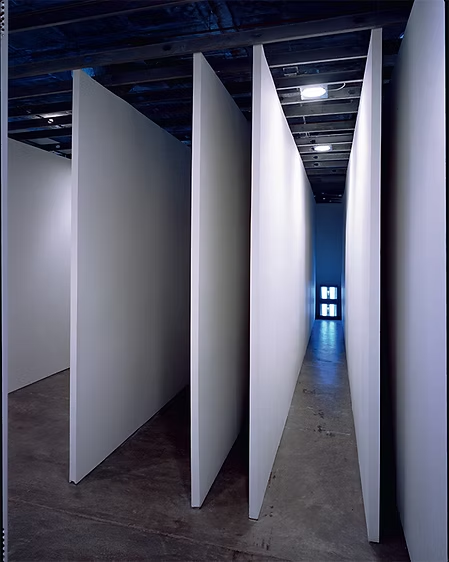

Bruce Nauman, Live-Taped Video Corridor, 1970.

Bruce Nauman, Live-Taped Video Corridor, 1970.

Wallboard and video devices. Guggenheim Museum.

Sleep, 1964, one of Warhol’s first ‘non-stopping’ movies, strikes its audience with a profound recognition of both the familiarity and the unfamiliarity of time. On the one hand is the supposed projection of “real-time,” suggested by events on screen that seemingly unfold in synch with the actual event. On the other is a recognition of ‘reel time,’ or diegetic time only relevant to a specific artwork or context. In Sleep, Warhol notably appropriated the ability of newly invented technology, the camera, to record separate footage of his lover sleeping and merge them to create an illusion of ‘pinning down’ real-time. However, upon closer examination, the audience recognizes that time even in Sleep is no more than an illusion; a red herring that again banishes the spectator to one’s subjective chronology.

While the debate regarding the experience and existence of time dates back to Aristotle, artists during the mid-late 20th century have attempted to address the matter in the context of and via mass media and film technology, often regarding their abilities to make the present and the past coexist - and in some cases, willfully contradict. Works that embody this trend markedly place the audience in a voyeuristic position, as spectators of a somewhat scopophilic nature who exist simultaneously inside and outside of the spatiotemporal context of the artwork.

For instance, in Bruce Nauman’s Live-Taped Video Corridor, 1970, the viewer witnesses oneself recorded on a monitor from the back while walking down a narrow corridor. The discrepancy between the actual figure and its recorded representation on screen is a crucial element, as it signifies both the audience’s full emersion in the artwork’s ‘reel time,’ while highlighting a total detachment from it in favor of each audience’s individual perception of ‘real time’ and space. Through his work, Nauman further questions the amorphous nature of reality in the contemporary era, subjected to reimaginations and manipulation by not only individual perception but also as represented and endorsed by media and technology. Furthermore, he notably enacts both the spectator and the camera as voyeurs, perhaps in criticism of organized surveillance enabled by postmodern technology.

Published date: Jun 22. 2025

Francis Bacon, Three Studies for Figures at the Base of a Crucifixion, 1944.

Francis Bacon, Three Studies for Figures at the Base of a Crucifixion, 1944.

Oil paint on three boards. Tate Britain, London.

During World War II (1939-1945), the horrors of war directly befell Europe. In Britain, one of the last bastions to resist the rapid spread of German Nazism, over a million urban homes were destroyed under strategic bombing. 40,000 civilians were killed, and 150,000 per night were forced to retreat into bomb shelters for survival. Even after the war ground to a halt in 1945 with the surrender of major Imperialist and Fascist powers, its utter horrors continued to haunt the living. Further exploration of Nazi concentration camps and hearings of war criminals revealed sadistic and meticulous methods of control and genocide, while nuclear detonations on the Eastern front highlighted a chilling premonition of mass destruction. On the one hand, the clamors of this bleak war spurred artworks that highlighted resilience, patriotism, and national identity across the globe. On the other, it evoked some artists, such as Francis Bacon from the ‘School of London,’ to visually portray its horrors and casualties through allegories and allusions.

In Three Studies for Figures at the Base of a Crucifixion, 1944, Bacon conjures a theme and format long-standing in the history of European religious art. Triptychs traditionally consist of three panels of separate scenes tied together by narrative or thematic coherence. In this work, Bacon retains the essential formation of triptychs but largely muddles the advent of readily recognizable icons and objects. Pale and bestial forms, coiled clearly in anguish, appear in each of the panels in a symbolic reference to the voyeurs of Christ’s death – and potentially in memorial of parallel sacrifices made on both the battlefield and the homefront. Bacon's statement that the three depicted forms allude to the Furies, or the three mythical Greek goddesses in eternal pursuit of vengeance, also introduces a sentient distaste against those whose hands have indeed been readily drenched in blood. Enveloped in an incomprehensible space against a hue of stark red, these creatures seem to exclaim in rage and powerlessness, their mutated bodies entwined in contempt against the unfathomable cruelty and malice of humankind that was once more rediscovered.

Published date: Jun 02. 2025

Shimon Attie, The Writing on the Wall, 1992.

Shimon Attie, "Linienstrasse 137," 1992,

from the series The Writing on the Wall, Berlin.

In psychoanalysis, projection is termed as a psychological defense mechanism that involves attributing one’s own undesirable traits and features onto external elements, dictating them as heterogeneous and harmful. Often exceeding logical boundaries, the projection of one’s unacceptable state and concerns may severely distort one’s perception of objective reality and manifest as expressions of racism, sexism, and xenophobia. In extreme cases, projection may occur collectively and foster a desire to cast out or exterminate the stigmatized or tabooed Other.

In modern history, the rise of Nazism could be interpreted as a collective projection of post-WWI Germany’s political and economic incompetence onto those excluded from a set model of superiority – most intensely targeting the Jewish population in Europe. Some of the most notorious tactics employed by the Nazi party, including propaganda, interrogation, and sociopolitical segregation, were deeply rooted in the mechanism of projection. The aftermath of the Third Reich thus demanded a process of actively rejecting or reinterpreting these projected aspects of identity for survivors in establishing post-trauma identities and memories. In the sphere of art, such a process involves not only the shedding of enforced identities and commemorating of memories but also a proliferated rebuilding of forfeited cultures and ways of life.

Shimon Attie’s 1991 work The Writing on the Wall exemplifies such attempts by projecting photographs of Jewish life in pre-war Germany onto the modern streets of Berlin both literally and figuratively. Attie’s work evokes nostalgia and loss by drawing forth the images of the now seemingly decadent past onto the spaces of the present day. Simultaneously. The public manifestation of these photographs also signals a conscious reclaiming of Jewish identity against that dictated by others or sociopolitical circumstances. While appearing as ephemeral specters, Attie’s projections nonetheless embody an ongoing struggle to persist in the face of a devastating past. By visualizing historical trauma and striving to rebuild individual and collective identities in an active reexamination and recontextualization of often suppressed heritage and memories, Attie successfully reverts the long-stagnant gaze of external projection.

Published date: May 06. 2025

Cildo Meireles, Marulho (Swell), 1991-97.

Cildo Meireles, Marulho (Swell), 1991-1997.

Pirelli HangarBicocca, Milan.

A wooden dock stretches out toward the end of a cubic room. The subtle blue hue of the walls corresponds with the vibrant colors knitted upon the floor to create a melancholy yet confined atmosphere. At first glance, the materials underneath the dock seem to be tiles organized in a pattern to resemble a body of water. Only upon closer inspection does the audience notice what’s under their feet is not liquid or tiles, but thousands of cut-out pages containing photographs of seawater. In Marulho (Swell), 1991-2001, Cildo Meireles, a Brazilian sculptor and installation artist, invites the viewers to indulge in an experience loaded with critical references to Brazil's political history and magical realism through the imagery of an ocean without water; or an abundance of information without truth.

In 1964, the Armed Forces of Brazil executed a coup that resulted in a military dictatorship spanning over two decades. During its regime, the Brazilian junta executed an extensive political manhunt against dissidents, much of which ended up in torture, murder, and unofficial disappearances of civilians of opposing parties. One of its most notorious policies conceived during this time was the Restrictive Constitution (1967), which sought to mutilate any voices against the government. Mouths were sown as propaganda published by the government sought to legitimize its authoritarian atrocities through enforced silence.

During and after the era of the Brazilian dictatorship, artists including Meireles attributed to speaking out against the junta through their artworks. Marulho, among Meireles’ outstanding collection of installations, seems to most directly, while nonetheless in a poetic manner, attack the creation and distribution of false information during the regime. Marulho exhibits the idea of an ocean that serves no practical purpose as an ocean but nonetheless deceives the viewers in the justification of its existence: a ‘swell’ of information that demands to be the truth. Meireles’ meticulous choice of iconography is chilling not only because of the ocean’s capability to consume but also because of its ability to flow away. Upon delving into the historical truth behind Marulho, the audience realizes that it is the duty of the learned to remember. In underlining the fine distinction between truth and those that pose as it, Meireles argues that some memories should never be forgotten; that no water under the bridge should flow in oblivion.

Published date: Apr 06. 2025

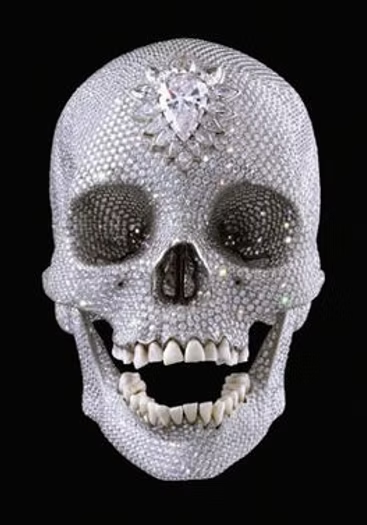

Damien Hirst, For the Love of God, 2007.

Damien Hirst, For the Love of God, 2007.

Diamonds and human teeth. White Cube Gallery, London.

While the cultural and emotional value of an artwork often greatly surpasses the price of its materials, art has admittedly generated a dense market of commissioned luxury throughout its history. In the last several decades, through the expansion of materials and the advent of the Readymade, the size of the art market in both its subjects and budget has expanded exponentially. Upon its traditional value as the manifestation of the human experience, art in the contemporary era is viewed also as an epitome of high culture and a subject of material investment. The resulting conversion of artworks into luxury goods was perceived initially as an alarming phenomenon by many. During the 1960s-70s, various anti-capitalist and anti-institutional movements arose among bands of artists, rejecting the dictation of commercial values in art and furthermore institutional and economic confinement.

On the other hand, artists such as Damien Hirst readily embraced the presence of marketing and economics in the art world. A human skull literally coated by painstakingly crafted pieces of diamond, Hirst’s For the Love of God is one of the most highly invested pieces of sculpture in the history of art. While the very existence of the piece itself seems to scream out nothing but profit and investment, its core subject matter alludes to the heritage of vanitas still life paintings and their universally symbolized principles of memento mori - 'remember you will die.' Although Hirst’s leap from the conventional readymade trope - items of the everyday incorporated into art - was deemed excessive and even absurd by many critics, his diamond-covered skull nonetheless exerts a spectacular attempt to transcend both the boundaries of the object and comment on the existential dilemma of death.

Furthermore, For the Love of God, in all its extravaganza, is a work that seems to simultaneously embody and critique the role of the material in the expanding art market. The theme of mortality and vanity, semiotically embedded in the image of the skull, immediately draws a stark and even parodic contrast to the instantly recognizable items of luxury that embroider its surface. Hirst's choice to layer a human skull purchased cheaply from a thrift store with over 200 grams of diamonds presents a scathing commentary on the contemporary dictation of material value upon not only materials of art but also the physicality and dignity of the human being now similarly commodified.

As a readymade object, Hirst’s diamond skull is one endowed with the privilege to move between aesthetic and cultural zones. The essence of the piece lies both in its 'flashy' presentation and its relatability with the rising standards of the contemporary art world. As a sculpture that embodies both material extravagance and the subject of unconquerable death, For the Love of God exclaims to its viewers and critics as did the proud Pharaoh Ozymandias: “Look upon my works, ye Mighty, and despair!”

Published date: Mar 06. 2025

Dahn Vo, We the People, 2011-2016

Dahn Vo, We the People, 2011-2016, copper.

At first glance, the constituents of Dahn Vo’s sculptural project We the People appear merely as independent pieces of scrap metal waiting to be recycled or disposed of. Scattered across their exhibition space in oblique and even precarious angles, these constructs also evoke the public installations by Richard Serra and Anish Kapoor. Passing across the landscape and around the materials, the viewers may recognize their resemblance to elements such as draped cloth, linked chains, and human fingers. However, like the blind men in old folk tales who fail to distinguish the coherent shape of an elephant, the viewers fail to grasp the ‘bigger picture.’ The designated fragmentation of Vo’s sculptural work, by design, appears also an initial mystery.

Dahn Vo’s We the People (2011-16) is a multipiece installation and sculptural project featuring an actual-sized copper replica of the Statue of Liberty fragmented into around 250 individual particles. Conceived in Germany, manufactured in China, and distributed worldwide, Vo’s sculpture serves as a potent metaphor for the inherent multiplicity of viewpoints upon, as well as the postmodern disintegration of, ideals such as liberty and democracy in the global context. As Dahn Vo intends, the pieces forming We the People will never be merged into a whole, in the same way that the constituents of the world will never, and should never, reach a total unanimity in their opinions and aspirations.

In his project, Dahn Vo demonstrates the deconstruction of an internationally recognized icon into its building blocks, posing a critical perspective on the abstract and often subjective concept it represents. His work thereby overturns the modernist notion of a coherent ‘single narrative’ which often swayed to sociopolitical power and served in the Western world as a justification for colonialism. As Vo highlights, one person’s progress might be another’s downfall, and one’s notion of liberty may parallel the exploitation of another. The use of copper, a material historically associated with colonization and economic exploitation, further highlights the economic dimensions of power and freedom across history.

Published date: Feb 06. 2025

Emily Prince, The American Servicemen and Women who Have Died in Iraq and Afghanistan, 2004-

Emily Prince, The American Servicemen and Women who Have Died in Iraq and Afghanistan

(But Not Including the Wounded nor the Iraqis nor the Afghanis), 2004-Present.

Pencil on vallum, Saatchi Gallery, London.

Emily Prince’s series The American Servicemen and Women Who Have Died in Iraq and Afghanistan consists of thousands of square vallum slips pinned to the wall. Each slip, slightly larger than the size of one’s palm, depicts the pencil-sketched portraiture of American soldiers who were killed in the Iraq and Afghanistan wars. The portraitures are paired with the name, date of birth, and date of death of the corresponding individual. Some slips include a short obituary, provided by the soldiers’ family and friends as well as the artist herself. Since its conception in 2004, Prince has closely monitored America’s warfare in the Middle East, and the vallum squares were added to the real-time records of those fallen in battle. By its exhibition at the 2007 Venice Biennale, the project amounted to a montage of five thousand slips, each aligned according to demography to form an abstract map of the world.

The American Servicemen and Women Who Have Died in Iraq and Afghanistan, in both its fragments and its whole, is an intricate portraiture of the human cost of war. The artist’s commemoration does not stand on grandiose martial ceremony but a tolling materialization of personal testament. Each vallum square manifests in solemnity and respect, resembling rows of gravestones in a military cemetery. Prince’s meticulous rendering of each face evokes a sense of personal connection, forcing the viewers to confront the toll of war on an individual level. Furthermore, Prince’s method asserts a powerful critique of the abstraction of war and its casualties. By bringing the faces and stories of the soldiers to the forefront, the work contends the tendency of political memorials and mass media that often detaches the public from the realities of conflict and presents the dead as a tallied number rather than a tragic loss.

Published date: Jan 06. 2025

Robert Morris, Mirrored Cubes, 1965.

Robert Morris, Untitled (Mirrored Cubes), 1965.

Mirror, glass, and wood. Tate London.

In her 1979 article "Sculpture in the Expanded Field," art critic and theorist Roseland Krauss argues against the common perception that the development of artistic trends and expertise occurs in static and gradual motion. Rather, Krauss asserts that across the histories of most crafts occur certain defining moments that trigger abrupt and encompassing reorientation of structure and boundaries. To Krauss, the contemporary initiation of the "expanded field" in sculpture is one of such ground-breaking progress. In highlighting the decay of the 'hero on a pedestal,' Krauss notes that sculptures from the 1950s forward strove continuously to break away from the conventions of format and institution that had previously bound the artwork and its experience to a limited site of context and display. Instead, contemporary sculpture establishes a critical autonomy: a self-inclusion of context and a blurring of its relations with the surroundings. In the 'expanded field,' sculpture often operates in the sociocultural field and not within the boundary of conventional materials. The artist and viewers alike are thus beckoned to explore the variable tableau of possibilities and combinations between sites, landscapes, and structures.

Cubes of simple geometric form are scattered around the pasture, seeming to merge and disappear into the surroundings. As if in camouflage, the objects' surfaces lined with mirrors readily absorb the environment and create a fluid optical illusion. However, in Mirrored Cubes, the reflection is key, and the illusion is secondary. Morris' cubes, in a deliberate design, constantly embody and respond to the space around them, as if to reflect the infinite experiences and phenomena of an ephemeral world. The spectators, in their physical interaction with the mirrored surfaces, unearth the artist's salient argument that sculpture exists not in a vacuum but innately in relation to the dynamic and ephemeral human experience.

Morris' sculpture is one that expects participation and naturally fosters interaction between the viewers and the artwork. While classical sculptures concentrated mainly on presenting compelling - and often authoritative - imagery upon designated pedestals and rigidly distinguished positive and negative space, contemporary sculpture in the 'expanded field' intentionally blurs such boundaries. Instead, installations such as Mirrored Cubes signal a departure from the self-contained art object and stretch the viewer's experience into the habitat and cosmology of the artwork. The entire environment regarding the sculpture, including the site of the exhibition and the spectators, becomes participants or more fundamentally, a part of the artwork that embodies all but itself.

Reference

Krauss, R. (1979). Sculpture in the Expanded Field. October, 8, 31–44. https://doi.org/10.2307/778224

Published date: Dec 15. 2024

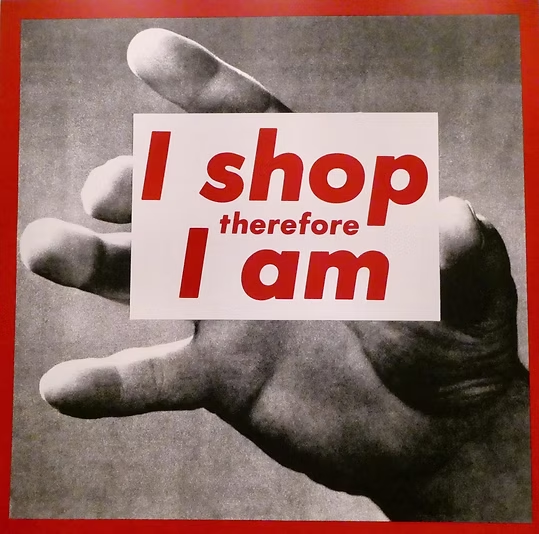

Barbara Kruger, Untitled (I shop therefore I am), 1987.

Barbara Kruger, Untitled (I shop therefore I am), 1987.

screenprint on vinyl, Los Angeles County Museum of Art.

For many contemporary artists, the proliferation of the readymade whether as a commodified object or a mass-produced photographic image activated the onset of not only novel visual aesthetics but also the possibility to address and reframe relevant sociopolitical phenomena by utilizing objects akin to life and its exceedingly material nature. As an incredibly flexible tool, the readymade was adapted to address various issues of the postmodern world, often from an ironic and critical point of view.

From the 1970s, Barbara Kruger gained significant recognition within the American art world for her photographic projects, which often consisted of black-and-white photographs – images drawn from all aspects of contemporary media, including films, television shows, and magazines – imprinted with bold red text boxes. The white of the textual slogans written inside these boxes generates a stark juxtaposition of color reminiscent of the styles and compositions widely utilized by advertisements and even wartime propaganda. That these texts often include pronouns – ‘I,’ ‘you,’ ‘we,’ and ‘they’ – that directly address the subject of their declaration further reverbs the immediate and emotionally potent prose of commercial texts and images that saturate the living conditions of today.

Untitled (I shop therefore I am), 1987, is a work especially representative of Kruger’s artistic trajectory. A photograph of a hand occupies the near entirety of the panel, its fingers lightly holding a scarlet text box towards the viewers. The text “I shop therefore I am,” a reimagination of Descartes’s famous quote “I think, therefore I am,” commands the work’s tableau, highlighting Kruger’s critique that consumerism has become so integral to contemporary life that the act of choosing and purchasing goods have become equivalent to the psychological process of constructing individual and collective identity. The ubiquitous availability of objects in capitalist society is thus projected as a condition chronically integrated with the gratification of one’s existential needs.

Published date: Nov 05. 2024

William Henry Fox Talbot, The Open Door, -1884.

Barbara Kruger, Untitled (I shop therefore I am), 1987.

screenprint on vinyl, Los Angeles County Museum of Art.

For many contemporary artists, the proliferation of the readymade whether as a commodified object or a mass-produced photographic image activated the onset of not only novel visual aesthetics but also the possibility to address and reframe relevant sociopolitical phenomena by utilizing objects akin to life and its exceedingly material nature. As an incredibly flexible tool, the readymade was adapted to address various issues of the postmodern world, often from an ironic and critical point of view.

From the 1970s, Barbara Kruger gained significant recognition within the American art world for her photographic projects, which often consisted of black-and-white photographs – images drawn from all aspects of contemporary media, including films, television shows, and magazines – imprinted with bold red text boxes. The white of the textual slogans written inside these boxes generates a stark juxtaposition of color reminiscent of the styles and compositions widely utilized by advertisements and even wartime propaganda. That these texts often include pronouns – ‘I,’ ‘you,’ ‘we,’ and ‘they’ – that directly address the subject of their declaration further reverbs the immediate and emotionally potent prose of commercial texts and images that saturate the living conditions of today.

Untitled (I shop therefore I am), 1987, is a work especially representative of Kruger’s artistic trajectory. A photograph of a hand occupies the near entirety of the panel, its fingers lightly holding a scarlet text box towards the viewers. The text “I shop therefore I am,” a reimagination of Descartes’s famous quote “I think, therefore I am,” commands the work’s tableau, highlighting Kruger’s critique that consumerism has become so integral to contemporary life that the act of choosing and purchasing goods have become equivalent to the psychological process of constructing individual and collective identity. The ubiquitous availability of objects in capitalist society is thus projected as a condition chronically integrated with the gratification of one’s existential needs.

Published date: Nov 05. 2024

Marina Abramovic, The Artist is Present, 2010.

Marina Abramovic, The Artist is Present, 2010.

Performance at MoMA, New York.

Marina Abramovic, a Serbian conceptual artist and a pioneer in the realm of performance art, manifested a profoundly intimate and evocative experience in her 2010 piece The Artist is Present. Presented at the MoMA for a duration of three months, Abramovic’s work involved the artist sitting still and silent at a table in a public space prepared by the institution. Visitors and pedestrians were encouraged to sit across her at the table and establish a wordless conversation with the artist. While the composition of the work was simple and the artist’s gesture minimal, many of its participants recollected profoundly emotional sensations ranging across vulnerability, anxiety, connection, and solace. Some assembled online platforms to share their diverse, unconventional experiences of having the viewer’s gaze returned to them.

Clearly, the unmediated presence of the artist was both challenging and transformative, as it encouraged an introspective reflection of the self and inquired the essence of human connectivity. Abramovic’s fascination with the corporeal limits of the human body has always constituted her performances, sometimes taking the form of the artist’s radical vulnerability and deliberate self-harm. In The Artist is Present, Abramovic demonstrated a similar, if relatively nuanced, dedication to push the boundaries of her physical and mental endurance. Situating herself as an object of contemplation for over seven hundred hours, the artist herself became the art object entirely exposed to the gazes and impulses of her viewers. On the other hand, in her utter passivity, Abramovic had transformed herself into a medium of reflection that dismantled conventional barriers between the artist and the audience, between the artwork and the voyeur. The subversion of the one-way dialogue often perceived as a norm when viewing art was what pushed the participants to experience an unfiltered connection with and the utter intensity of human presence.

Published date: Oct 01. 2024

22El Anatsui, Earth's Skin, 2007.

El Anatsui, Earth's Skin, 2007.

Aluminum and copper wire. Brooklyn Museum.

While the value of an artwork often greatly surpasses that of its materials, it is admittedly true that the rapid expansion of the public market and the contemporary integration of high-end media into artmaking processes has generated works distinguished in both commercial relevance and sheer monetary value. Whereas the introduction of the readymade proliferated the transition of everyday objects and imagery into the art world, it has also functioned to further expand the scope of materials and themes in the creation of artworks. As Jeff Koon's monumental balloon sculptures and Damien Hirst's notorious For the Love of God. 2007, suggests, art remains in the contemporary era as both an epitome of high culture and a subject of material investment. The unchanged status of artworks as luxury goods and trophies of economic competence was perceived as an alarming phenomenon to many artists during the 1960s-70s. Anti-capitalist and anti-institutional movements during this time endeavored to drift away from dictating commercial values in art, while many artists shared the goal of escaping from the institution and thus cultural and economic confinement.

On the other hand, the growth of the art market has also signaled its extension out of the geographical and iconographical sphere of Western culture and across the global hub of varying aesthetics and social commentaries. Earth's Skin, a 2007 sculpture by the Ghanaian artist El Anatsui, introduces a striking synchronization of both. From a distance, Anatsui's sculpture curtained against the gallery wall resembles tightly woven sheets of nets or tapestry. Upon closer inspection, the audience realizes that the artist has crafted its material facade solely from recycled bottle caps and scrap metals woven together by copper wires. In creating Earth’s Skin, El Anatsui collected such discarded objects from local recycling sources in Ghana and Nigeria and sowed them together using indigenous tapestry-making techniques. His readymade is comprised of empty shells and fragmented commodities that had lost all practical value through the means of consumption. However, the artist's reformation and recontextualization of such materials highlight a triumphant proliferation of the marginalized and the abandoned, as well as a salient commentary on the tilted tables of globalization and the cost of blind consumerism that extends beyond the practical value of any medium.

Published date: Oct 01. 2024

Cindy Sherman, Untitled Film Still #10, 1978.

Cindy Sherman, Untitled Film Still #10, 1978.

Gelatin silver print. MoMA.

In accordance with nationwide activisms and the turbulent political climates in the United States, some artists of the 1970s and 80s depicted a heightened vigilance towards the potency of commercial imagery in the construction of sociopolitical norms and desirability. The ‘Pictures Generation’ epitomized this wave, sharing a common interest in critically examining the relationship between graphic visuality and individual and collective identities. Some artists delved into recontextualizing published images or experimenting with novel electronic media. Sherrie Levine, for instance, challenged the notion of the artist’s originality by appropriating existing photographs as readymade materials and situating them in wholly different contexts.

On the other hand, some members of the Pictures Generation expanded on the profound impact of the mass-produced ‘image’ on the construction and representation of the self. This was often achieved through appropriating and reframing established commercial figures. Richard Prince, by deliberately rearranging and omitting details of commercial photographs, critiqued the absurdly hyper-masculine symbol of the ‘American Spirit’ as embodied by the merchandised figure Marlboro Man. Cindy Sherman’s works, although far more integrated with the artist’s physical presence, flowed through similar veins.

Cindy Sherman’s series Untitled Film Still (1977-1980) consists of self-portraits meticulously staged to reflect certain personas or archetypes inspired by films and television shows. Due to their deliberate pictorial generality, Sherman’s photographs resisted the construction of original narratives and prompted the viewers to interpret them within their familiarity with generic and commercial tropes. Sherman’s goal was thus to encourage the viewers to reflect on the stereotypical and commodified portrayal of femininity perpetuated by visual culture. By explicitly embodying the characteristics of such images or becoming the stereotypical image herself, Sherman challenges and subverts these established norms. By utilizing fragments of existing images as readymade material, Sherman appropriates an oppressive monument of contemporary culture and transforms it through reversion. Her work sheds light on how the roles ascribed to identities are continuously shaped by the artifacts of culture which are becoming more ubiquitous by the day.

Published date: Sep 07. 2024

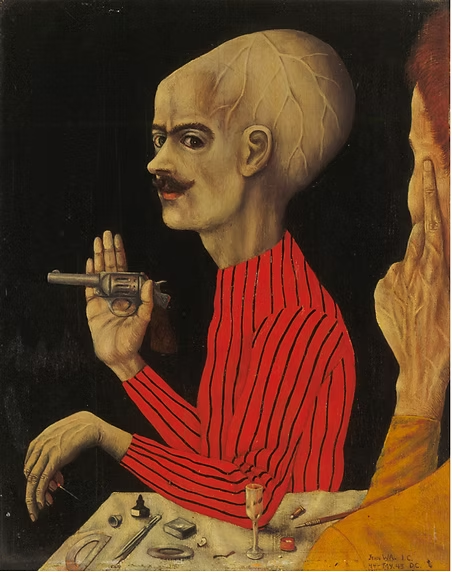

John Wilde, Exhibiting the Weapon, 1945.

John Wilde, Exhibiting the Weapon, 1945.

Oil on plywood panel, Chazen Museum of Art.

In Exhibiting the Weapon, 1945, American surrealist painter John Wilde indulges his viewers in a surreal visual game, offering scarce clues that point to an incomprehensible narrative. The warping of objects in both scale forms conjures a dreamlike ambivalence, while the painting’s central features produce a foreboding, and even ominous, atmosphere. The stark darkness of the surrounding backdrop in turn spotlights the people and objects depicted in the scene.

A man in a bright red pinstripe sweater holds up a revolver between his thumb and palm. Balancing the gun in his hand in no practical fashion, the man shows little intention of properly grasping the weapon or using it. Instead, he merely displays the weapon as one would show a hand of cards in a game. The man’s head introduces yet another enigma, as it is noticeably swollen with veins protruding on the surface. An adjacent figure whose face is not revealed to the viewer peers at his companion across the table, pressing his index finger against his temple. The table between the two figures holds a series of items, notably writing and drawing utensils, that appear disproportionately miniature.

Despite the protagonist’s apparent peculiarity, the gun he holds commands a more central presence within the painting. That a tool of violence is merely displayed and not wielded raises questions regarding the intention of its owner. The protagonist’s face provides scarce additional clues and instead gazes back toward the viewers as if to breach the ‘Fourth Wall.’ Wilde’s distortion of shapes and sizes further produces an air of ambiguity, hinting at a surrealist dismantling of plausible forms and composition that shrouds the artist’s intentions. The miniaturized drawing utensils may suggest a certain uncertainty or indifference towards one’s identity and expertise, while the figure’s mutated head alludes to an alienation from humanity, perhaps due to an indescribable catastrophe or the curse of ‘knowing too much.’ What, then, does the man know that the viewers do not? What does he intend to do with his weapon? Much like the protagonist’s ambiguous facial expression, this painting seems to raise more questions than it answers.

Published date: Aug 07. 2024

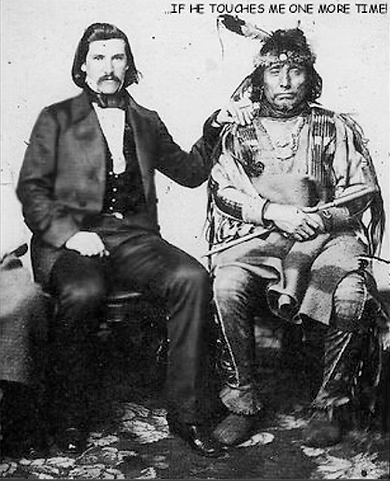

Hulleah Tsinhnahjinnie, Damn!…If He Touches Me One More Time! 1998.

Hulleah Tsinhnahjinnie, Damn!…If He Touches Me One More Time!, 1998.

digitally montaged 19th-century photograph, from the series Damn.

In her 2003 article When is a Photograph Worth a Thousand Words? writer and photographer Hulleah Tsinhnahjinnie addresses the chronically distorted frames of perception towards the sociopolitical Other, particularly focusing on the identities projected onto Native American populations such as the Seminole, Muskogee, and Dine clans. She highlights how ‘outsiders’ – or European colonizers – tend to reinforce stereotypes upon their beliefs and evaluations, leaving the marginalized communities stuck within preconceived notions. Tsinhnahjinnie’s study highlights the profound impact of mass-produced commercial imagery about, and the archetypes attributed to, these communities that continue to generate such a cycle of forfeited agency and visibility. Tsinhnahjinnie argues that such productions visually frame the subjects to no more than what has been predestined by the colonizer and diminish their unique presence through a leveraged reaffirmation of existing tropes and frames.

Tsinhnahjinnie’s notion of photographic sovereignty is thus poised to challenge and redefine biased conventions through the achievement of social visibility as well as a critical recontextualization of commercial imagery. Her artistic attempts mirror her determination to achieve renewed photographic sovereignty on both individual and communal levels. In Damn!... If He Touches Me One More Time!, 1998, part of her photographic series Damn, Tsinhnahjinnie appropriates a 19th-century vintage image by a non-Native photographer. In the photograph, a white man wearing a suit sits beside a Native American individual in traditional attire, placing one of his hands on the tribesman’s shoulder. This image, in its chronological setting, would have affirmed the colonizers’ notion of sociocultural hierarchy and served to justify their exploitations. Tsinhnahjinnie, in her altercation, gives a tongue-in-cheek voice to the depicted Native American figure, reshaping the narrative of the original image and revealing contextual aspects not conveyed by the photograph but essential, nonetheless. This approach brings the indigenous perspective to the forefront, allowing for the rightful expression of protestation and resentment.

Reference

Tsinhnahjinnie, H. J., "When is a Photograph worth a Thousand Words?" Photography's Other Histories, Durham and London, Duke University Press, 2003, pp. 40-52.

Published date: Jul 07. 2024

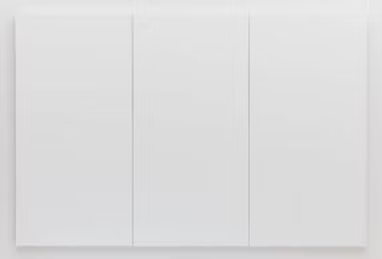

Robert Rauschenberg, White Paintings, 1951.

Robert Rauschenberg, White Paintings [three panels], 1951.

House paint on canvas, San Francisco Museum of Modern Art.

Emanating from the metropolitan and multicultural center of New York, many contemporary artists of the mid-to-late 20th century sought to expand the traditional tableau of artistic expression toward new horizons. Many placed a strong emphasis on aesthetic experimentality; the artist was now an agent of reform that would, through their works, overhaul academic conventions and reevaluate perspectives and existential conditions within the rapidly changing climates of post-war America. Novel ideas thus became as crucial as technical expertise. Some artists pioneered the diminishing of boundaries between ‘high art’ and popular culture, venturing outside the spatial constraints of the studio and museums into street corners and public theatres. Some arduously experimented with the amalgamation of diverse aesthetic elements such as photography, texts, and commercial objects. Portraits of pop stars now shared the stature of Mona Lisa and Girl with the Pearl Earrings, and collages of images drawn from mass-produced media reflected the nation’s exceedingly hybridizing lifestyles and identities.

On the other hand, conceptual art largely emphasized the situation of the work in a state of performance, often incorporating the audience’s interactions with the artwork as its primary feature. Conceived in 1951, Robert Rauschenberg’s White Painting saliently reflects the artist’s expanded role as the performer of ideas and disruptor of norms. Influenced by the American composer John Cage and his infamous piece 4’33,” Rauschenberg aimed to portray on canvas the notion of absolute passivity. White Paintings was conceived as a triptych of panels painted entirely white and devoid of any depicted forms. As the audience’s discord and conversations become the main constituting elements of Cage’s composition, the intended content of these monochrome paintings would not be the artist’s performance but rather the light, shadows, and occasional debris produced by the environment and cast upon the blank canvases. While Rauschenberg’s work itself understandably met polarizing reviews, the artist’s boldness continued to heavily influence the medium-specific aesthetics of Minimalism and its central notion that art should occupy its own unique reality and converse emotionally with its audiences.

Published date: Jun 12. 2024

Liu Xiadong, Jincheng Airport, 2010.

Liu Xiadong, Jincheng Airport, 2010,

oil on Canvas, MoMA, New York.

Eight casually dressed individuals are gather around a folding table, immersed in an ongoing trump card game. Some participants lower their heads in ponderation, while some playfully shift their cards. Surveying the spectacle, a figure brings a cigarette to his mouth. This is a friendly match, with the players waging not money but the time and camaraderie they have cultivated with each other. Two figures standing at the left of the circle, although not in the game, seem to be deeply engaged, perhaps occasionally voicing an exclamation of concern or excitement.

In the background emerges an airplane that extends over the figures’ heads. Although it appears as a resilient monument, the many wears and tears on its steel surface make it clear that the vehicle has endured considerable age and weathering. It now stands, retrieved from action, in tribute to an era of valor in which it has marked its name. As if to counter the aesthetics of the machine’s cold steel, the vegetation of vibrant colors spread around the vehicle, encompassing the scene with a rich wreath of green and gold. Liu’s subtle integration of the depicted individuals and the retired aircraft suggests their pictorial roles as metaphorical testaments of China’s modern and contemporary history

All the figures depicted in Jincheng Airport are friends or peers of the artist, proud locals of this illustrious countryside. Their close acquaintance is noted in the painting and amplified by Liu Xiadong’s expressed resolution of naturalism that aligns with the theorist Walter Benjamin’s concept of the aura – the emotional essence of a cognitive experience that strikes the viewer with ritualistic power. In Jincheng Airport, the artist’s nuanced yet expressive rendering of formal elements collectively constitutes a scene conceived from realism but enforced with an experienced attempt to depict beyond transient forms. For both Liu and Benjamin, the most essential qualities occur spontaneously and in uncomplicated terms.

Published date: May 12. 2024